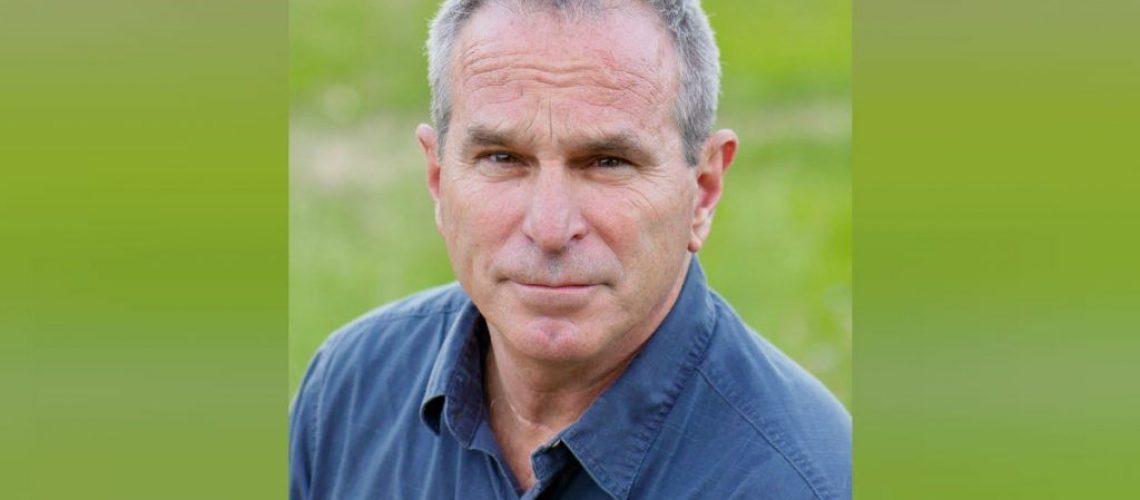

Book Reviewer: Deb Ryan

The Fracking Debate is a fantastic book for anyone that is curious about engaging in the energy conversation. Raimi takes us on a journey from the early stages of the unconventional shale revolution in 2011 to the volatility of 2016, all through conversations he had with people living and working in oilfield towns all across America.

The Debate

As the title indicates, this book is truly a debate. Highlighting areas of research and experience from the people living in oilfield towns to address the good and the bad aspects of the shale revolution. Like most things in life, the truth usually lies somewhere in the middle.

Even though this book was published in 2018, the discussions and conclusions are possibly even more relevant today than they were then. We all have our own fracking debates, with friends, neighbors and sometimes family with our own preconceived ideas and biases based on how the industry has impacted us directly, or indirectly through stories and what we read in the media; and this book does such a good job of balancing out the discussion, for both people who work in the industry, and those who don’t.

Raimi covers questions that include “Does Fracking Contaminate Water?” “Will Fracking Make Me Sick?” “Does Fracking Cause Earthquakes?” and “Is There Any Regulation on Fracking?”. These are all critical issues in the fracking debate, and I implore people to go and read Raimi’s book for the details. I want to highlight some key issues that I took away from the “Is Fracking Good or Bad for Climate Change?”, “Is Fracking Good for the Economy?” and “Do People Living Near Fracking Love it or Hate it?” in relation to public perception and the impact of the industry.

Methane Emissions

Methane emissions are a huge issue in the Climate debate. As Raimi points out, “methane is 72-87 times more powerful a greenhouse gas then CO2 over a 20-year time frame” and that if “roughly 4% of gas production was released as methane the climate impact would be the same as coal”.

Wait, what!?

The oil and gas industry has used the “we are a better option than coal” argument extensively. Raimi goes through different studies and approaches in detecting methane, and how reliable (or not) some of these measurements are. He also points out that when methane emissions are just looked at on a large scale, oil and gas is not the only contributor. Agriculture, land fills and coal mining also have a role in this. But, at the end of the day, what Raimi does point out, is that methane is an issue. It’s a solvable issue, but it is one that the oil and gas industry needs to address throughout the entire supply chain, from production to consumers. And if the oil and gas industry doesn’t take the lead in solving this issue, it will find that regulations will force the change, which is starting to be seen in some states already.

The Economic Impact

I am a firm believer that decisions relating to the production and consumption of energy are first and foremost economic ones. For companies, for governments and for individual consumers. From 1998 to 2014, Raimi points out the growth in GDP contribution of the oil and gas industry goes from 0.4% to 1.7%. This 2014 GDP contribution was $294 billion dollars, and that is just from companies themselves, not the indirect spending in oil and gas communities.

Governments have been able to bring in tax revenues and for a lot of consumers it has meant access to cheap and affordable oil and natural gas. The downside though is the boom-and-bust cycles, which is especially felt in the oilfield towns. Local prices sky-rocket and infrastructure is built, only to have the bust cycle hit and everyone leave town again. Those that work in the industry are aware of these boom and bust cycles, but for the local communities the effects can be devastating.

How to Move Forward From Here

The final chapter in Raimi’s book addresses public perception. The biggest take-away I took from this, is that for the most part, those that live and work in oilfield towns, are accepting of the oil and gas industry and “the good outweighed the bad”. It was Raimi’s comments about returning to the city, to “Ban Fracking” signs that really struck accord with me.

Why does proximity to the oilfield towns impact how willing people are to support the oil and gas industry? Given that recently we have seen rolling blackouts in major cities and small towns all across the US due to nation-wide cold weather, maybe there is an opportunity to figure out how we can continue the debate that Raimi covers so well, and maybe, just maybe figure out how to have better conversations about energy.