Originally Published on MIT Sloan Management Review, 11/3/21, written by Katie Mehnert

In recent years, calls have increased for people to be better allies to coworkers who are members of marginalized groups. Millions of people believe they have heeded those calls. In a LeanIn.Org and SurveyMonkey survey conducted in June 2020 — as protests over police killings of unarmed Black people were sweeping across the country — more than 80% of White people said they see themselves as allies to people of other races and ethnicities.

But people who are supposed to be on the receiving end of such support often see things differently. Of Black women respondents to the survey, only 45% said they have strong allies at work, and only 26% said they believe Black women have strong allies at work in general.

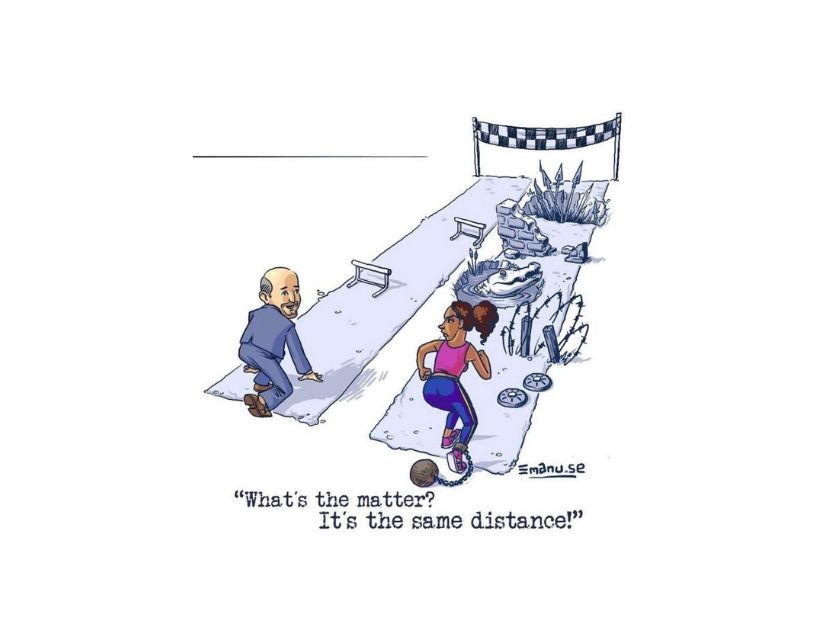

New research from McKinsey and Lean In sheds light on why this allyship gap persists. The survey found a disconnect between what women of color say are the most meaningful actions of allies and the actions that White people prioritize. For example, White employees believe that speaking out when they see discrimination is the most meaningful step. But women of color, especially Black women, say the most meaningful step is to advocate for new opportunities for them.

Similarly, a 2019 survey found that 77% of men believed they were doing all they could to support gender equality at work, while only 41% of women agreed. LGBTQ+ activists have also long noted that well-meaning allies often don’t understand what they should and should not do, including at work.

As a White woman who spent years as a corporate change leader in the field of energy and then left to create an organization focused on diversity and inclusion in the sector, I have experienced both sides of this. I have sought out allies to help stand against sexism and all forms of bigotry. I’ve also sought to be the best ally I can be to people of color. Through this combination of experiences, I’ve come to see how employees can become more effective allies.

1. Learn how prejudice manifests.

Allyship must begin with learning about all the impediments a group of people runs into. For example, the McKinsey/Lean In study found that women of color were experiencing just as many microaggressions at work as they had two years earlier. Unfortunately, this is not so surprising, because even many self-declared allies don’t recognize microaggressions when they happen.

As four professors wrote in Harvard Business Review, the first step in becoming an effective ally is to educate yourself. Learn about prejudice and the many ways it shows up. Take the time to do this on your own. Read books, watch TED Talks, and listen to podcasts.

To help educate employees, organizations and industrywide events should invite expert speakers to address these topics. (Numerous speaker bureaus make such experts available, and I recommend watching videos, when available, to see previous talks these speakers have given.) After making such topics a central theme at events for the energy industry and conducting webinars and interviews with women of color, I’ve heard from attendees that they’ve learned new ways to spot bigotry.

2. Take guidance from those you wish to support.

With a deeper understanding of the issues, a would-be ally is then ready to take the next step: learning from colleagues exactly what steps would be most helpful to them. As two women of color and I discussed in a webinar last year, this must be done carefully.

For your colleagues who are members of a minority community, “it is not their responsibility to be your teacher,” said Paula Glover, president of the Alliance to Save Energy. Without assuming that they’ll drop everything to talk to you, be an active listener. Notice anytime a colleague points to a form of prejudice they face — whether in a meeting, as a quick aside, or as part of a conversation on another topic.

It is OK to ask people how you can help them. But do so without asking them to set aside an hour to talk you through it — and, again, without expecting them to be responsible for educating you. For example, I like when people write me a quick email asking me steps they can take to help women at work. I often send a quick note back with a couple of links that lay out my top pointers, such as, “Give women a merit-based seat at the table,” and “Make gender equality a strategic value that you measure.”

When people tell you what steps are most helpful, actually take those steps. Your actions show that you’re committed to true allyship. Colleagues are then more likely to engage in longer conversations with you. As Shantera Chatman, global culture strategist and president of PowHer Consulting, puts it, you have to “work to build the trust” first in order to get into a discussion of such sensitive subjects.

3. Remain steadfast.

Allies need to be persistent. When advocating for someone to get a job opportunity, you may find hiring managers judging a female candidate by different criteria from men, or writing off a candidate of color as a “poor cultural fit.” An effective ally will argue on behalf of the candidate and point out unfair practices.

This persistence also means withstanding pushback. Last year, I sent a message to board members, clients, and connections about the dangers of “White silence” amid racism. Some people reacted with anger or concern, saying that I should not discuss controversial topics and that I could lose business as a result. I kept speaking out anyway. I may have lost some business because of this, although no one said so directly. I also received a lot of support — and, understandably, questions from some people of color as to why I had not spoken out about this sooner. I had no good answer. I resolved to do better, listen, and learn what actions I should be taking. Being a committed ally requires a willingness to be called out on your failures and to keep growing.

By following these steps, anyone can become an ally. It’s not about getting everything right; it’s about continuously doing the work. As the number of effective allies grows, the allyship gap will get smaller — and our organizations will become stronger.

Originally published: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/tackling-the-allyship-gap-at-work/